Two Different Standards

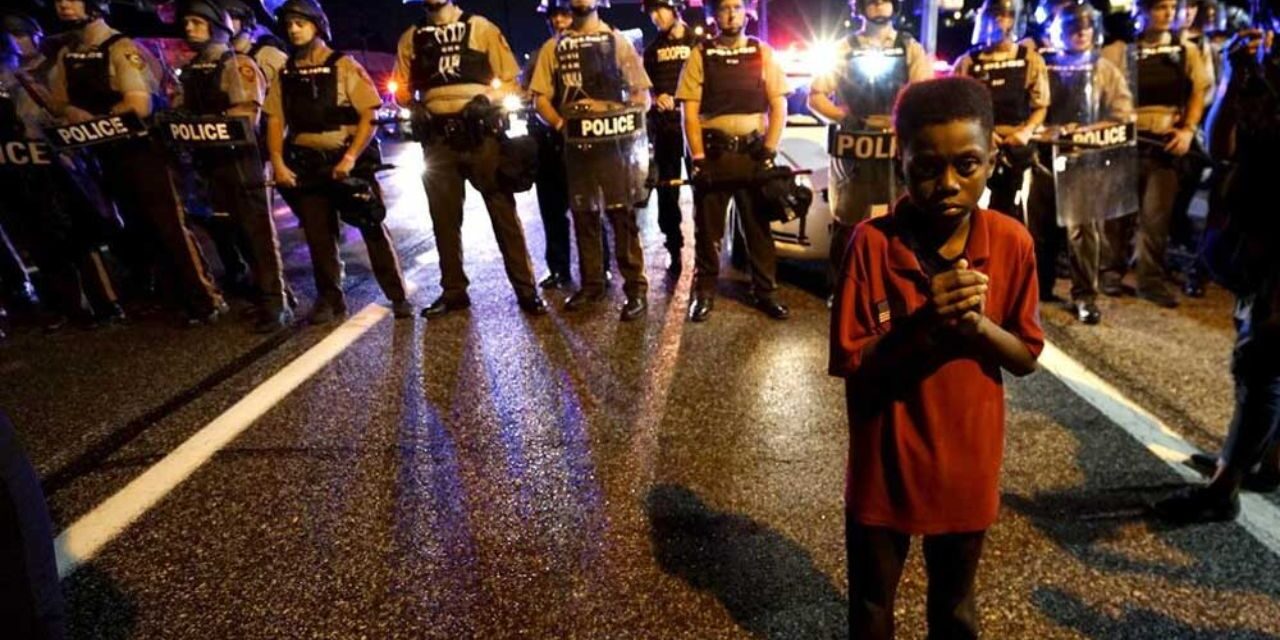

While growing up, I had to learn unofficial rules that my white male counterparts did not have to worry about. While they were worrying about acne breakouts, girls, learning to drive, and moving up (or down) the social hierarchy of their school, I was stressing about more serious matters. Matters that have proven to result in incarceration, and even life and death. A great example of this is what black boys in America are taught about the police. Here’s a story from my adolescence about my first police stop. To put into context, this story happened well before the Black Lives Matter movement and all the publicity about blacks being killed by police officers.

My First Police Stop

It was a hot, Atlanta summer day. High school was out, and my fifteen-year-old self is now a newly minted Georgia learners permit holder. My focus were on driving my mother’s car each and every chance I get, trying to meet up with girls at the local mall, and working on my basketball game. Today, the girls will have to wait, though; In the morning, the team and I were going to Tallahassee, Florida for a week to play in a high school basketball tournament. I can’t wait!

Currently, I was packing to go. I go through the list of items to make sure I don’t forget to pack anything. Basketball shoes? Check. Water bottle? Check. Warm-ups? Check. Armbands? No. Where are my armbands? I conclude that I don’t have time to search the house for the armbands, so I have the wonderful idea of rounding up two of my black friends, let’s call them Dante and Larry, and driving ourselves to the local mall. I can buy new armbands, and I get to drive again and possibly meet a nice, young lady. Win-Win-Win. I ask Greg, a 20-something-year-old black male who is a friend of the family and staying with us at the time if he doesn’t mind chaperoning. He obliges. 15 minutes later, two of my friends, our chaperone, and I are getting in the car. Greg sits in the passenger seat, and Dante and Larry get in the back. Before I pull out of the driveway, Greg orders us to put on our seat belts. He then proceeds to warn me to follow all rule and regulations while driving on the road. I agree and off we go.

Less than a mile after pulling out of the subdivision, I see a police car in my rearview mirror. I inform the occupants of the car, but I don’t panic. Why should I? We’re not disobeying any laws. No sooner did these thoughts run through my head, the police cars lights come on.

I pull off the road and halfway into the grass on the shoulder. I wait for the policeman to approach. Five minutes go by and he still is not approaching the vehicle. Then, two more police cars pull up.

After a while, the first policeman, along with another officer approaches our car from both sides. The first policeman walks up to the driver’s side door. He has a stern look on his face. One hand is on his gun in the holster. Without greeting or announcing what we are being pulled over for, he asks for license and registration as well as the IDs of all occupants in the vehicle. We hand it over to him. He then instructs all of us to raise our arms and put our palms on the ceiling of the car while he goes back to his vehicle. I suspect to check us out. I am still relatively calm. I’m on my mother’s insurance and thus have the legal right to drive her car. Furthermore, I have a responsible adult in the car with me. We are good. Nothing to worry about.

Thirty minutes go by and we still have our hands up on the ceiling. I know because I keep looking at the clock on the dash. Why? Because my arms are burning. I want to put them down, but I don’t dare. I am not alone in my thinking. We all are voicing our displeasure. My friend Dante is especially unhappy and complaining the loudest. Finally, the first policeman returns with our IDs, and something else… a warning citation.

The officer starts out by making mention that the reason he stopped us is that he thought he smelled marijuana, but it turns out it’s probably the grass under the car burning. This doesn’t make much sense, but we don’t argue. He then proceeds to give the warning citation to Dante. Dante asks why he’s receiving a citation, and the policeman explains that he wasn’t wearing his seat belt when he approached the vehicle. Dante contends he was, and the rest of us know he is telling the truth. This is when Greg speaks up. Greg shortens our discussion with the officer by simply thanking him for doing his job and allowing us to be on our way. We breathe a sigh of relief. I start the engine up. We are heading not to the mall but home, no one is in the mood to go to the mall anymore. We just want to get away.

The rest of the short ride home is quiet. When I pull into my driveway, we all exit. Dante stomps off in the direction of his house, citation in hand. Before going our separate ways, Greg turns to Larry and I and says, “Don’t hang out with Dante. He going to get y’all killed.” No need to elaborate. We know exactly what he means.

What We All Knew

Years later, I told this story about my first police stop to a white friend of mine. She had so many questions: Why does the policeman need backup for a routine stop with just teenagers in the car? Why did you not argue with the officer if you knew Dante was compliant and had his seatbelt on? And, how is Dante going to get you killed?

The better questions to me were, how did the black males in the car follow standards from some unofficial manual they all seemed to read? And why were we so relieved when the police encounter only resulted in a citation? This wasn’t a new phenomenon. Blacks within the community have always talked about how to carry yourself when interacting with police for fear of the encounter turning into an arrest, or much worse, death. For some reason, at the time of the story Dante had not had that talk in his household yet, but the pattern nonetheless is noticeable. Larry, Greg, and I, three black males growing up in three different households all knew that as a black man in a traffic stop, we should be as compliant as possible and try and not give the officer a reason to shoot you. We were all taught this.

Dante Was Right… Sort Of

Now that I’m older, I know Dante was right… sort of. Greg in his compliance was only trying to keep us safe, and I thank him for it, but allowing law enforcement to do and act however they want is not right. Dante had reason to be upset. However, there are other ways to handle it than arguing with an officer with a loaded weapon; more effective ways that other law-abiding, tax-paying citizens follow such as contacting the officer’s superiors and filing a formal complaint.

Black males’ number one priority should be to keep themselves safe. After that, they should seek justice. Do not let law enforcement treat you worse than others because of your race. Do not let law enforcement treat you negatively when you’ve done nothing wrong. I leave you with a quote from the late Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

“For evil to succeed, all it needs is for good men to do nothing.”