by Brian Fitzgerald (Guest Post)

In my humble opinion, words are the most powerful things the human race possesses. They have started wars and they have ended them. They have even created constructs as powerful as laws and religions. That is why the words we choose to emphasize in the field of criminal justice should be chosen with great care.

Two of the most popular words used in criminal justice throughout history include rehabilitation and its counterpart, punishment. Both are powerful words with opposite meanings. However, somewhere along the way in the field of criminal justice, the definition of rehabilitation was twisted to include punishment. As such, one of the greatest cognitive distortions of all time was uleashed on the American public.

So where did it all go wrong…

Early in the twentieth century, the criminal justice word of choice was rehabilitation. The rehabilitation of offenders was central to mainstream thinking, because “fixing criminals” seemed like the right thing to do. As such, incarceration was widely seen as an opportunity to fix the criminal offender. Unfortunately, where it all went wrong was that the “fixing” was being done via punitive means. More or less, criminals were being punished into submission.

Therapeutic interventions were unheard of at this time. There was experimentation on criminals, but that’s a whole other story…

Needless to say, rehabilitation wasn’t working (for obvious reasons), so by the 1960’s and 1970’s the political climate shifted away from that word. Instead of looking at punishment, skepticism about the appropriateness and the effectiveness of rehabilitation grew. To the public, it sounded like criminal justice was being soft on crime – even though in reality it wasn’t.

So what did the great thinkers do? They simply removed rehabilitation all together and went to war… Something that always makes things better, right?

In 1965, President Lyndon B. Johnson determined that criminals must be punished. This is evidenced by his telling Congress, “I hope that 1965 will be regarded as the year when this country began in earnest a thorough and effective war against crime.”

When Richard Nixon was elected in 1968, he continued this “war on crime,” and blamed crime rates on the leniency of the criminal justice system. He said that the “solution to the crime problem is not the quadrupling of funds for any governmental war on poverty, but more convictions.” And we wonder why so many poor people are in our prisons today…

In time, as the goals of crime control and offender accountability ascended, long-standing principles that limited harsh punishment receded from political debate and crime policy. The magnitude of the increase in incarceration rates after 1972 and the speed with which it occurred demonstrate the transformation of the purposes of punishment.

According to the American Civil Liberties Union, the U.S. has nearly 25% of the world’s prison population, despite making up close to 5% of the global population. Since 1970, our incarcerated population has increased by 700% – 2.3 million people in jail and prison today, far outpacing population growth and crime.

Fast forward a bit… On October 27, 1986 President Reagan signed into law the Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1986. Its main result was to create mandatory minimum sentences. The harsh sentences on crack cocaine were used disproportionately against African-Americans.

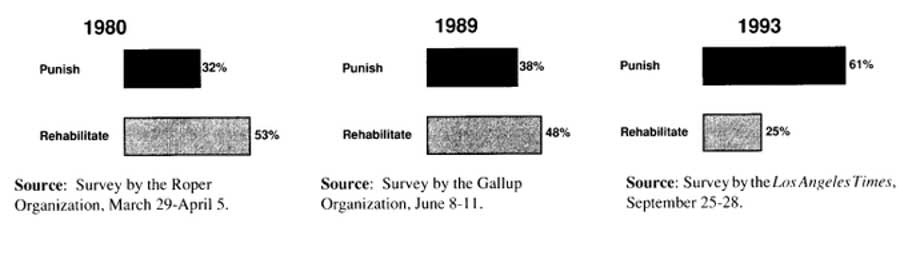

All of this build up for justifying a tough on crime stance reached its peak in 1993. That year, more Americans believed the primary purpose of prison was to punish, not rehabilitate. So finally, America agreed that it was okay to punish criminals, even though that’s what we had been doing all along…

This opened the door for President Clinton to pass the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994, which the administration presented as both tough and smart on crime. The act allocated more money for prisons and issued harsher sentences, including a three-strikes law. Twenty-four states passed three-strikes laws between 1993 and 1995.

President Clinton would later admit that the three-strike law was one of his biggest regrets. Speaking to a civil rights group in 2015, he said: “I signed a bill that made the problem worse and I want to admit it.” It put 100,000 more police officers on the streets but locked up “minor actors for way too long.”

Only recently have leaders started to think about incarceration differently. My hope is that 2020 will be the year that “transformation” becomes the word that is used to describe the purpose of prison. People need to leave prison better than how they came in. They need to have the skills and opportunities to become better people, not people that are more broken, more violent, and better criminals.

About the author:

Brian Fitzgerald is a writer and criminal justice reform advocate. He can be reached at brian@fitzmg.com